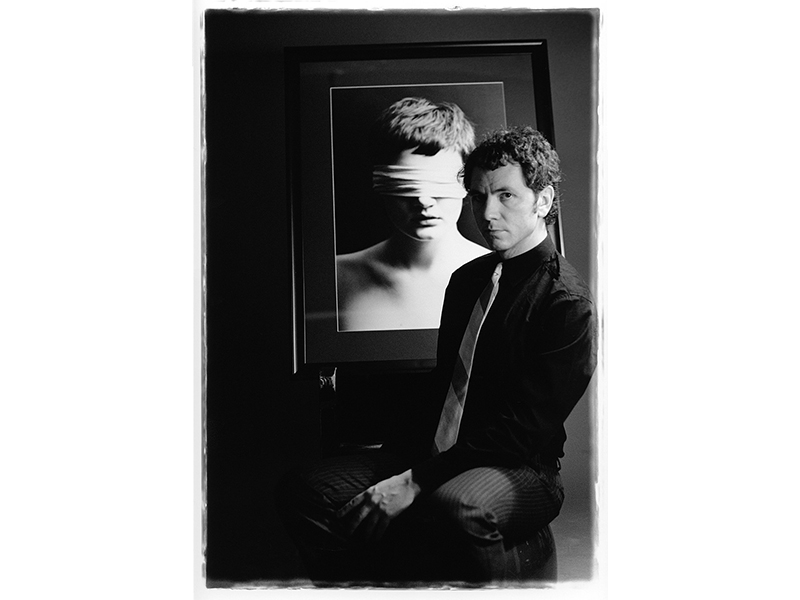

Francis A. Willey

Local photographer learned firsthand the blessing and the curse of digital culture

A decade ago, Francis A. Willey went viral before most people were even aware there was such a thing as going viral.

The Calgary photographer, pianist, dad, and one of the publishers of the fine photography magazine SEITIES was a local artist who created uniquely beautiful portraits, often in sepia tones, shot in such a way that they evoked the turn of some other long-ago century.

It was a combination of fashion, old-style portraiture and sensuality that was shot on 35mm film, and developed in a dark-room, using Verdant Luminul, Willey’s (and partners Bruce Hildesheim and Sanja Lukač’s) environment-friendly recipe of non-toxic, natural developing fluids for black and white photography.

Willey was an emerging local fine artist—until around 2003, when along came Myspace, the first genuine social network with mass global appeal.

He may have been an old-fashioned 35mm photographer, but as far as digital marketing and branding went, he was an enthusiastic early adopter.

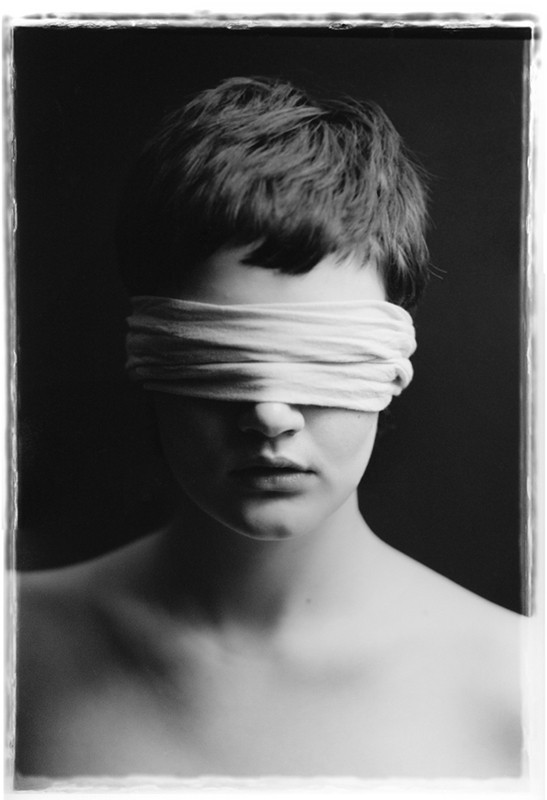

At the time, he had a new body of work, including a sepia portrait of an androgynous-looking model with a sash wrapped around their eyes.

He called that photo Blindness.

He also had recorded some new piano music, and Myspace was then offering musicians and bands a great new way to showcase themselves.

“I thought, I’ll just put my art on there, and share my photos and my music for the first time,” he said. “See what happens.”

What happened was both the blessing and the curse of digital culture.

“All these artists were connecting with me, celebrity types, fashion designers—because it was a new playground for people that were expressive. And it was safe,” he says.

Willey’s photographic images attracted attention. He found himself getting invited to participate in a number of art exhibitions in different corners of the planet. He got published by Italian Vogue and various other international publications.

“I was given all these art opportunities. I was pretty much living in my art studio at the time, com-posing music and printing work and doing photo shoots non-stop—just absurdly obsessed with creating bodies of work, all these things to share these experiences and to be bold,” he says. “So I was offered these shows, and decided to take a Berlin show.”

Of course, when you’re an independent artist, and the father of two young daughters, living off your art, getting to an art exhibition in Berlin is as much of a challenge as getting into it—not only is the plane ticket expensive, so is the cost of shipping the art.

Willey got himself to Berlin. Barely.

“Your whole life is as an artist. I never applied for any grants—23 years,” says Willey, a self-proclaimed outsider artist. “It’s all been art piece by art piece, photo shoot to photo shoot–and I’m not a commercial artist.

“And even when I do photo shoots, I have a sliding scale in my rates, he continues. “It depends on the person’s background and what the photos are for.”

It was Fashion Week in Berlin in 2007. Mercedes Benz was the sponsor. There were parties and art everywhere.

And then Willey discovered that one of his images—Blindness—was, too.

Only it wasn’t exactly his version of Blindness—or it was, but he discovered his photograph had been re-purposed by people he’d never had any contact with.

“That image of the blindfolded face ended up being on posters everywhere,” he says. “A couple graffiti artists escaping the tyranny of Iran, had taken it off the wall and made their own stencil of it.

“They started graffiting it as a statement against their government—and then they were launched into the international art world and were being interviewed about creating this art piece.”

And then, things got even weirder.

“Then Lou Reed shared it on the internet, and it just became this crazy thing,” he says.

A little while later, now back home in Calgary, Willey received a message from a friend in New York.

“Out of nowhere, a friend of mine named Levi, contacts me and goes, congrats on being published in New York,” he says. “He saw in something like in the New York Times, or a blog by one of the New York Times writers and I was like—really?”

Back to the internet search engines he went, where he discovered someone else—not the Iranian graffiti artists—had used Blindness.

“I found out my image was being used as an example of blind gossip, for a celebrity story,” he says.

After Levi explained the reverse image search mechanism, Willey did one for Blindness—and discovered that the image was everywhere, being used by dozens of different arts organizations, non-profits, publishers, and individuals.

There was even an organization in Rajasthan soliciting for eye donations that used Blindness in its advertising campaign.

It was simultaneously flattering, inspiring even—many of the messages were ones Willey himself endorsed—at the same time it was exasperating.

Because in not one single instance had anyone acknowledged that Francis Willey, of Calgary, Alberta, was the creator of Blindness.

It was almost as if he had written a #1 song that he received neither credit nor royalties for.

One day, Willey went for a pint at the Ship and Anchor, where he told the story to poet Kirk Miles, who suggested he turn the experience of having his artwork being globally appropriated into a whole new art installation.

“I just did a series of photos where I basically put on my website 101 memes of 380 that I’ve found,” he says. “In total, I probably have over 4,000 examples of where my art has been borrowed or used for something else.”

The images are used to promote just about anything you can imagine, in every area of every society, in dozens and dozens of languages. (Google Blindness and the image usually is one of the first four that comes up).

“Some of them are a little more heady than other things. Some of them are laughable, and I don’t care about them. Some are intriguing—some I think are really interesting,” Willey says. “It’s got-ten to that point where most people have seen that image. It’s become such a cultural thread in all languages, all religions.

“So I gathered the memes, put them on the website, and put a Blindness appropriation gallery.”

In 2012, Willey was invited to New York to feature his appropriation piece in an art exhibition.

That led to meetings with various lawyers about the possibility of pursuing various organizations or corporations or individuals for copyright infringement—but the catch is that once you finish paying a lawyer to chase down a copyright infringement, the only person really making any money is the lawyer.

In the meantime, life has gone on.

Willey and partners and co-creators Sanja Lukač and Kirsten White have built SEITIES—it means personal identity—into a viable non-profit magazine, with a board of directors, making it eligible to receive funding.

Willey’s work has been exhibited in New York, Paris, Berlin, Los Angeles, Italy—and in places like the recently-departed Swerve Magazine in Calgary.

His photos are in the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography and included in the National Gallery of London archives.

Even his piano work has received international attention—one day, a video of Willey performing was featured on the website of the New Music Express in Britain—although he regards his music as a bit of a sideline gig.

At this stage of his career, and life—the young daughters are now teenagers, and Willey is re-covering from a broken femur he incurred slipping on his icy city sidewalk while taking his daughters dog out for a walk in 2017—he is more sanguine about the role Blindness has played in his creative life than he is determined to chase down the thousands of people using it without attribution or payment.

He’s just as thankful for the small miracles in his life—like that time, in 2011, when his house caught fire, destroying much of his work, and killing his cat, but somehow not the negatives for Blindness.

Still, after living a life as truly creative as it gets, he admits it would be nice if people actually knew who created Blindness.

“Even if there’s accreditation—my name—I’d be fine with it,” he says. “Then people would know who created the image.”

What’s not in doubt is that Blindness expanded his world beyond what he could have ever imagined.

“That blindfolded image—and putting art on the internet—got me to Berlin.”

The original photograph Blindness can be viewed at the Lightbox Studio in Arts Commons (205 8th Ave. SE) until October 29, 2018.

About The Storytelling Project

On November 16, 2015, Calgary Arts Development hosted a working session with approximately 30 creative Calgarians from various walks of life. Many of the small working groups voiced the need to gather and share more stories of people living creative lives.

On November 16, 2015, Calgary Arts Development hosted a working session with approximately 30 creative Calgarians from various walks of life. Many of the small working groups voiced the need to gather and share more stories of people living creative lives.

That need has turned into The Storytelling Project.

The Storytelling Project raises awareness about Calgarians who, by living creative lives, are making Calgary a better city, effecting positive change and enriching others’ lives.

Have a story to share? Email us at news@calgaryartsdevelopment.com.