Patricia Grimwood

The do-it-yourself ethic has never gone out of style for prairie people

When she was a teenage girl in the 1990s, the daughter of a single mom living in the Calgary neighbourhood of Woodlands, Patricia Grimwood couldn’t afford the jeans the cool girls wore at school—the ones with brocade fabric on them—but she could sew.

“Woodlands was then a fairly affluent neighbourhood,” Grimwood says. “There were kids who had super nice clothes, and we didn’t, so I had to learn to sew myself because I wanted what they had.

“I discovered,” she says, “I was good with my hands.”

Soon, she created jeans that passed the cool test with her classmates.

“I made them the best of those jeans in the school,” she says. “And then I said to the other girls at school, yeah my mom bought them.”

It wasn’t an accident that Grimwood was good at making stuff, either—it was part of her family’s DNA, where everyone learned that if you wanted something, chances were better you’d get it if you learned how to make it yourself.

That sort of do-it-yourself ethic is hip now, in a 21st century marketplace filled with craft beer, Etsy, and an

obsession with locally-grown food, but it never went out of style for prairie people.

The story behind the story of Grimwood’s sewing prowess goes back—way back—to the early days of the 20th century, to rural Saskatchewan, where Grimwood’s grandparents lived on a homestead, back to a time in history when Western Canada was raw and unbuilt—and isolated from the rest of the world.

“When I was little,” she says, “my grandmother had one of those… cast iron treadle sewing machines and my grandpa would sew on it.”

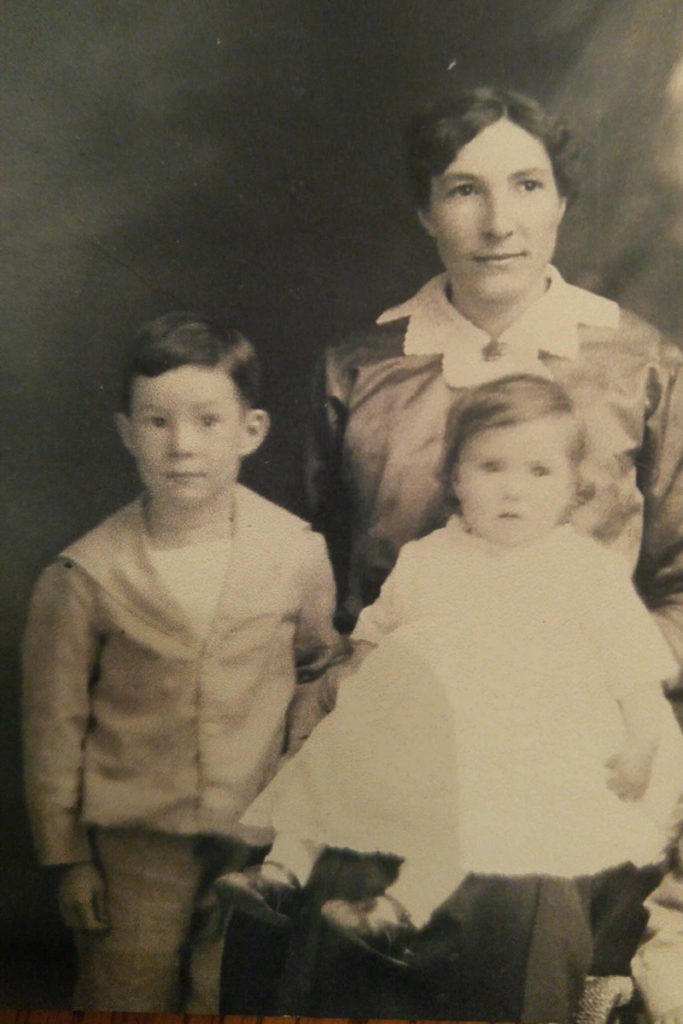

“His mother was a teacher, a Metis woman, in rural Saskatchewan,” she adds. “When she was married, she gave up teaching, as one did in those days. When she had children, she would gather them round her at night and teach them. Anything they wanted to learn, she would teach them.

“Grandpa wanted to learn sewing. He was born shortly before the First World War—not really a thing that boys did.

“I remember Grandpa sewing pajamas, he could sew anything,” she says. “He just sewed. What I took from that is that there was really nothing that I couldn’t create.”

Nowadays, Grimwood is a Calgary single mom, of a tweener, 12-year-old daughter, who puts those Saskatchewan homesteading lessons to good use.

She makes jam. She preserves vegetables. She makes pickles and spice mixes. She took a tanning class to learn how to sew leather. She even makes her own soap.

Grimwood has turned everyday activities into the opportunity to live a creative life. And what you soon discover with Grimwood, is that learning to make stuff is a story every single time out, even when everything goes wrong.

Like the time she was 21, when she decided to make homemade soap for her boyfriend’s mother’s birthday present.

“I was in a second hand bookshop,” she says, “and they didn’t have any novels. That was when I saw a soapmaking book, so I picked it up, and made my first batch of soap—and it was horrible!”

Grimwood had no scale. The recipe called for weights, rather than measurements—so she had to guess the proper amount of ingredients to add. She didn’t have a stick blender, so she couldn’t mix the recipe of mainly fat and lye properly. She added lilac blossoms, which turned black. She left the concoction to set, and it turned into a soupy, vomity sort of stew that refused to solidify, even after two weeks, so she threw it out in the garden, turning the soil into a place where nothing grew.

All of which raises the question: why go to all that trouble, when you can just go over to Shoppers Drug Mart and get some soap?

“That question could apply to everything I do that I could just buy,” she says.

When she’s not plucking lilacs off the tree in the backyard to transform them into a bar of soap, Grimwood has been trying to write down some stories, to express her life through words as much as she does with her every day living.

Her latest is in the form of a letter to a famous novelist.

“I’ve been thinking really heavily about Joseph Boyden,” she says, of the award-winning Canadian author who has been at the middle of a hot literary debate after being accused of culturally appropriating his Indigenous identity.

“He says he has some Indigenous ancestry,” she says, “a small amount of Indigenous blood actually, but that it forms a large part of his identity.

“What troubles me about that,” she continues, “is that he doesn’t have the intergenerational experiences of people who do have Indigenous ancestry.

“I can’t say this for sure,” she says, “but if he doesn’t have this experience and the myriad of micro experiences that go along with it—both positive and negative—then he’s telling the wrong story. He’s

telling Indigenous stories through the settler’s gaze. Telling our stories through that gaze was never right.

“There are great Metis writers, there are great First Nations writers, there are great Inuit writers who are telling the truth,” she adds. “One of Canada’s greatest problems is we don’t tell the truth. We tell comforting lies. This is 2017 and we are still not teaching our children in schools what actually happened, what actually birthed this nation, what our wealth in this nation was built on.

“The whole Dear Joseph Boyden letter I’m writing is the result of the fact that I am a Metis woman with white skin privilege,” continues Grimwood. “I can pass as white, my family passed, but passing comes at a cost. And I’m introducing my child back into her culture, and giving her what was denied me because it was safe.”

Why live a creative life? Why make the soap yourself?

“I just like to do things myself,” she says. “I always have. If I can do it myself, if I can be self-sufficient in that way. You see, that’s the thing: I don’t think of it as living a creative life. I just think of it as self-sufficiency.

“That’s why it’s important. Rather than going to someone else who has the same skill set as I do, I have the time to do it myself to my specifications… so having the ability to make something that I love completely—that’s important to me. And it’s easy to learn how to make something—or to be taught,” she adds. “I love the idea of traditional knowledge being passed along.”

About The Storytelling Project

On November 16, 2015, Calgary Arts Development hosted a working session with approximately 30 creative Calgarians from various walks of life. Many of the small working groups voiced the need to gather and share more stories of people living creative lives.

On November 16, 2015, Calgary Arts Development hosted a working session with approximately 30 creative Calgarians from various walks of life. Many of the small working groups voiced the need to gather and share more stories of people living creative lives.

That need has turned into The Storytelling Project.

The Storytelling Project raises awareness about Calgarians who, by living creative lives, are making Calgary a better city, effecting positive change and enriching others’ lives.

Have a story to share? Email us at news@calgaryartsdevelopment.com.