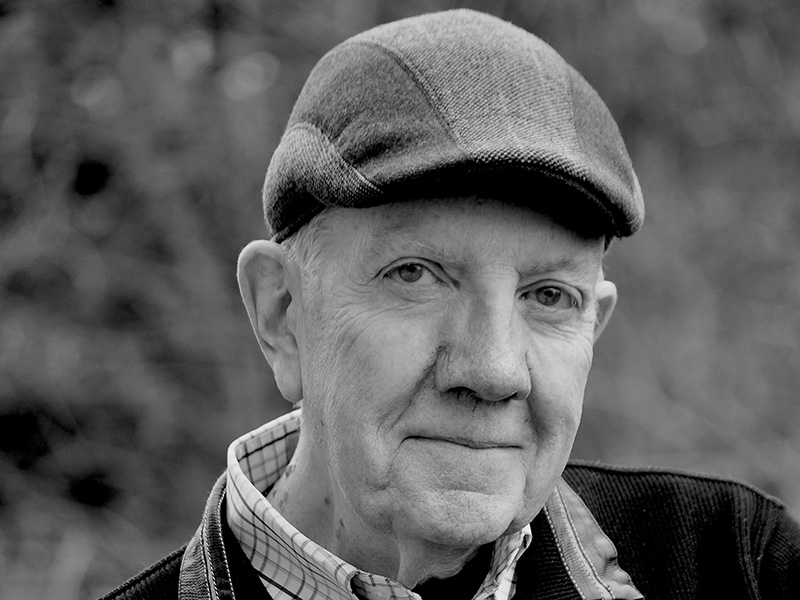

Brian Brennan

If you just do things in life for money you’re missing out

In 1974, Brian Brennan had two job offers. One was to work as a reporter at the Vancouver Province, the other from the Calgary Herald.

The Vancouver gig was a 90-day trial run, that may or may not have turned into full-time employment.

The Calgary gig was full-time, permanent.

“I didn’t want to come to Calgary,” said Brennan, who grew up in Ireland, before immigrating to Canada in 1966, starting in Vancouver and then Toronto.

“But I had a wife and a five-year-old daughter,” he adds. “So I told my wife we’d do a year in Calgary.

“That was 1974,” he said.

That turned out to be thousands of Calgary theatre reviews, feature stories, obituaries, and 16 books ago.

Brennan’s first novel, The Love of One’s Country, which blends his Canadian creative life with the narrative of the Irish potato famine and exodus in the 19th century, was published in early October.

The book launch was at Owl’s Nest Books in Britannia.

Five decades in, Brennan, who turned 76 a week before the novel’s publication, and his wife are still here.

“Longest year,” he says, “of my life.”

Brennan’s creative life started at seven, back in Ireland, when his mother got a piano, despite the fact the family really couldn’t afford one.

By the time he was in high school, Brennan was the de facto leader of the orchestra whenever the drama department produced a musical.

That talent was generally utilized playing for fun in clubs around Dublin, after work and on weekends for seven years, where Brennan worked in the civil service, until the age of 23 when he and his musical partner decided to try Canada for a few years.

They got day jobs in Vancouver not unlike the ones they’d had in Ireland, and continued to play gigs around town, until one night in 1966, in a Vancouver club, they were spotted by a Dawson City, Yukon theatre impresario who liked their blend of Irish folk songs and scathing parodies of Irish folk songs.

He offered them each a thousand a month, for the summer, and expenses, too.

They took the Dawson City gig, and left day jobs behind—or so they thought.

After summer was done, they relocated to Toronto, signed up with a popular booking agency, and in short order, found themselves regularly sent out on the road.

Their brand of Irish melody and Irish cheek worked for club owners across the country. Those were the days, in the 1960s, when clubs booked acts for six nights a week.

Brennan and his partner found themselves working regularly around southern Ontario, and the pay, for the late 1960s, wasn’t too shabby: $600 a week apiece, plus hotel, transportation, and usually dinner and bar tab as well.

The only problem was that Brennan wasn’t built to be a touring musician.

Truth be told, living life as a touring musician didn’t feel terribly creative.

“Play the same songs, night after night,” he says. “It starts to drive you nuts after a while.”

He was the truly rare bird: A successful musician who really preferred a day job.

Brennan would write letters to his girlfriend on the road. She thought his writing showed potential.

“She said, you ought to do something with that,” he says, which led to a long, fruitful, and creative spell in the newspaper business, at the Herald—even if the starting wage was $100 a week, a far cry from what he earned as a musician.

At the Herald, Brennan was the theatre critic in the 1970s and 1980s, there in the early days of Calgary’s emergence as a creative city.

There were a few bumps.

His first review was the Stampede Grandstand Show.

“I panned the Young Canadians!” he says, with a tone that suggests he knew that was going to provoke a few readers to respond.

Letters to the editor followed, but Brennan, undaunted, continued to review Calgary theatre as he saw fit, which meant calling them as he saw them.

He also panned Theatre Calgary’s first installment of A Christmas Carol and found himself banned twice by Stage West, which didn’t appreciate his blunt assessments of several of their shows.

And there were also plenty of raves, as well as growing up as a critic at an exciting time, when both Sharon Pollock and John Murrell were coming of age as playwrights, and Theatre Calgary—thanks, in large part to artistic director Rick McNair—and Alberta Theatre Projects were emerging as major players in western Canada’s theatre ecology.

He also spent time as a reporter on the paper’s weekly magazine, who was given the rare luxury of spending weeks researching lengthy features.

But Brennan’s creative life as a newspaperman was truly triggered writing about the dead.

“The conventional way to do an obit is to write what really amounts to a eulogy,” he said. “I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to sort of reinvent obit writing.”

Instead, Brennan turned the obituary into a kind of feature story, where he interviewed a single person, and then wrote a profile that tried to capture the best self of that individual.

There was one, about a Calgary upholsterer who quit upholstery to try Nashville as a singer-songwriter.

Brennan interviewed the upholsterer’s daughter, who tried to describe what made her father tick the best way she could.

“She said, I guess the wild horses have to run with the wild horses,” he says. “I thought, that’s beautiful. That’s really, really nice. That’s one of those little nuggets that you hope for when you interview somebody.

“I wouldn’t write the story like, then she said this about him and then she that about him,” he adds. “I would write it as if I’d known the guy—as if I had gone to Nashville with him, and sat in with the band on the stage.

It was a completely different approach to obituary writing that connected to the family members and friends who shared their stories with him.

“The nice thing was the reaction that came back was, ‘I liked the way you told my dad’s story,’” he says. “It was almost as if you knew him.”

That all changed in 1999, when Conrad Black resisted efforts by the Herald newsroom to unionize.

Brennan found himself out on strike, although he even managed to turn that into a creative opportunity.

“I wrote my first two books out on strike,” he says. “So it wasn’t all bad. And there was a lot of freelance work available in those days as well.”

Many of Brennan’s non-fiction titles explore the origin story of the people who built Alberta (Building a Province: 60 Alberta Lives, Boondoggles, Bonanzas and Other Alberta Stories; a bio of Ernest Manning; the official history of the Calgary Public Library).

There have been others that were more personal and connected to his Irish roots (Leaving Dublin: Writing My Way from Ireland to Canada).

But it took until he was 76 to publish his first novel, which blends the autobiographical with an almost mythological exploration of Irish history told through the eyes of a fictional character from the 19th century, who goes on a journey similar to the one millions of impoverished Irish people did in the 1840s.

He was always working on it, but found it difficult to release it into the world.

There may not be a second one.

“I’m 76 next week,” he says. “If I was in my fifties, maybe. I’m going to be a little bit like—not that I want to compare myself to him—but Alistair MacLeod, who basically only wrote one novel.

Sometimes, I guess you can say the same about Harper Lee.

“Sometimes, one is sufficient. Who knows? The muse hasn’t paid me a visit recently, so could be short stories.”

Why does it matter to live a creative life?

“If you just do things in life for money,” he says, “you’re missing out.”

On November 16, 2015, Calgary Arts Development hosted a working session with approximately 30 creative Calgarians from various walks of life. Many of the small working groups voiced the need to gather and share more stories of people living creative lives.

That need has turned into The Storytelling Project.

The Storytelling Project raises awareness about Calgarians who, by living creative lives, are making Calgary a better city, effecting positive change and enriching others’ lives.

That need has turned into The Storytelling Project.

The Storytelling Project raises awareness about Calgarians who, by living creative lives, are making Calgary a better city, effecting positive change and enriching others’ lives.

The Storytelling Project raises awareness about Calgarians who, by living creative lives, are making Calgary a better city, effecting positive change and enriching others’ lives.