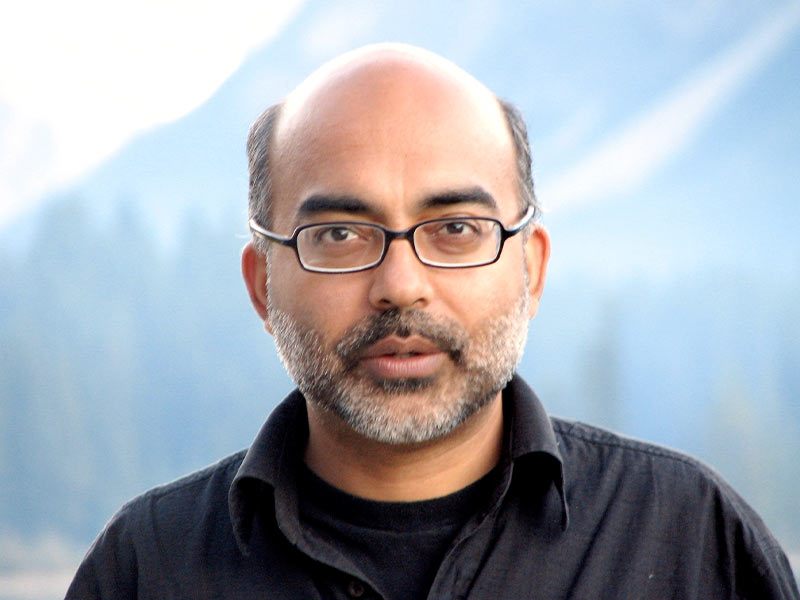

Jaspreet Singh

Author finds his creative sweet spot in the Rocky Mountains

Calgary author Jaspreet Singh’s creative life started with a rock.

Or, more precisely, with a mountain.

“Years ago I stood on a nameless rock in Banff, half-submerged in the Bow River, and it was there I made the decision to become a writer,” he said, in an interview with me for CTV late in 2021. “Walking around in the Rockies, I experience marvelous silences. I witness the blurring of multiple scales: the planetary, the human, and things deeply personal.”

He’s not kidding about the deeply personal part, either. Singh, who has enjoyed a remarkable 12 months in which he has had both a memoir (My Mother, My Translator) and a new novel (Face: A Novel of the Anthropocene) published “after a long silence,” has been based in Alberta for the past 15 years. During that time, he has written novels, short stories, personal essays, and poems, in addition to his most recent works.

One of those explores his youth, which was spent as a child in Kashmir, where he was constantly moving from one place to another. It turned out that Banff’s rocky vistas are a dead-ringer for the mountains of Kashmir, allowing Singh, who writes exquisitely about the sense of dislocation felt by migrants and newcomers to strange new worlds, to feel as if he’s right in his creative sweet spot.

“Mountains — no matter where they are on the map — are the only places where I feel at home,” he said.

Mountains play a central role in Face: A Novel of the Anthropocene as well. The novel is told through the first-person narration of Lila, a science journalist in her 30s who lives in Alberta but is equally consumed with an incident that took place in India years earlier. Present-day Lila covers the conversation around climate change and the constant jockeying for intellectual supremacy — and funding and status — that academics compete for as they market their expertise to the increasingly distracted digital world, where it’s necessary to spend as much time jousting with online trolls as it is researching academic journals, which it turns out are not exactly reliable narrators of the past.

Face: A Novel of the Anthropocene is a briskly-paced blend of storytelling styles, where the winner is the person whose story resonates the most with the public.

Singh, who in addition to being a fiction writer, poet, and memoirist, has a PhD in chemical engineering and worked as a research scientist for years prior to that fateful day on the mountain in Banff, brings a unique level of insight to the academic and scientific aspects of the story inside Face. When the conversation in the novel turns to one particular star academic’s controversial idea about seeding the skies in order to mitigate the impact of global warming, Face: A Novel of the Anthropocene feels urgent and necessary. Rather than being the excuse for a thriller subplot, what to do with our warming planet feels like the heart of it and Singh’s prose provides a reliable and frequently provocative guiding hand.

“I am not a trained geologist or climate expert,” he said. “I worked as a research scientist many years ago, but in a very different discipline.

“Perhaps my narrator (Lila) is a stand in for a lot of people,” he said, “People who believe in critical thinking and want to engage with the discourse and overwhelming emotions connected to climate change, people who are neither proper social theorists nor activists nor practising scientists.”

Somewhere in the middle of the book there is a fascinating exchange between Lila, the science journalist, and a climate scientist:

“What is the most astonishing thing for you working in the sciences?” I asked my favourite question.

“This ability,” she said, “this ability to switch from human time scale to geological time scale within a split second and talk about three billion years ago as if it were yesterday’s rain.”

“Why did you join the sciences?”

“Because as a teenage girl I was trying to process a single line once uttered by my maternal grandfather: Human civilization depends on geological consent.”

The story of Face itself was inspired by Singh’s own itinerant pre-pandemic life. He’s spent many years as the writer in residence at a variety of institutions, including the University of Calgary, University of Alberta, and the Calgary Public Library. But those writing residencies have also led to New Zealand and Europe.

“In 2018 I spent some time (by invitation) at an Institute of Advanced Studies for the Sciences in North Germany,” he said. “There were several climate labs in the area. I visited a lab, where I shadowed a glaciologist, who, among other things, gave me a tour of the ice-core archive.

“I was allowed to touch an ice core, its traces of a volcanic eruption several thousand years ago. A similar shadowing took place at a marine lab, where a deep-sea postdoc showed me a sediment-core archive, encouraging me to touch one, its traces of the fifth extinction, the end-Cretaceous mass extinction 66 million years ago that wiped out 75 percent of plant and animal species.

“The contact my hands made with deep time was something of a turning point, the beginning of Face.”

Equally mesmerizing are the stories he shares in My Mother, My Translator, a memoir told in a unique blend of what might be called literary fragments. It’s full of warmth and family memories of Singh’s own childhood, as well as the emotional impact of the trauma of Partition in 1947, when India was divided. Two million people died, and 15 million were displaced.

It’s a different story about a different time than the 21st century, but here we are in 2022 and the same images and traumas are being repeated over and over again, in Ukraine, Afghanistan, Africa, and Central America, as people move from home to somewhere new — and all the residual uncertainty and potential conflict that entails.

“The book, among other things, makes an attempt to process trauma(s) connected to the partition of India (by the British) exactly 75 years ago,” Singh said. “The 1947 partition created one of the largest refugee crises in the world.”

“No matter where one lives today (in North America or South Asia), one tries to engage with two important questions. How do diverse groups of people live together peacefully and with dignified difference in complex societies? How does a country, its citizens and institutions, work through the problematic histories of a place?

“The 1947 partition of India by the British is a significant dimension of the present, an unfinished history. My mother was a partition survivor. My father is a partition survivor.”

The impetus around My Mother, My Translator was the publication of 17 Tomatoes, Singh’s first book of short stories, in 2004. He wrote it in English. On a 2007 visit to Calgary (from New Delhi), his mom offered to translate it into Punjabi — except for one story that she took exception to. My Mother, My Translator is Singh’s journey into part of India’s complex history and its traumatic decoupling from British colonialism. At the same time, it’s a reflection on his own personal journey and unique story.

Through both Face and My Mother, My Translator, there’s a constant tension around the power of stories to shape our place in the world and our sense of ourselves.

In Face, narrator Lila reflects on the contemporary anxiety about our incredible shrinking attention spans, and the pressure that puts on storytellers. “The simple algorithm of his narrative tricks carries a built-in bias, I thought, and I raised my hand. Some of us are not against movement. I want things to move, I want thought to move. But to me, slowness is a quality as important as quickness.”

In My Mother, My Translator, Singh reflects on a variation on the theme: that the absence of a story is also a story. What’s he getting at there?

“The poet Rosmarie Waldrop has a marvelous book called Gap Gardening,” he said. “One becomes more and more aware of the gaps. Gaps are what make human beings really fascinating. Not filling in, but gardening in the gaps.

“For me ‘a lack of story is also a story’ has multiple meanings. In the book I also use the lack of story to convey the erasure of certain stories. Erasure of entire lives. Especially stories of women.”

Throughout Face: A Novel of the Anthropocene, there’s another tension: the gap between the way the human characters treat time and the way climate scientists think about it. For the people, time is minutes, hours, days, weeks, months. For a mountain, it might be tens of millions of years. Or three or four billion — all the way back to the start of time.

That brings Jaspreet Singh back to one of his favourite places on the planet: Banff.

“One particular mountain fascinates me immensely,” he said. “In the book I talk about the near-mythical Mount Yamnuska. For the longest time, this mountain kept geologists busy trying to figure out its secret. What confused the scientists was the presence of thick layers of old rock (550 million years old) that lay not below the deposits of young rock (78 million years old) as expected, but right above them. Normally old rock bears the weight of the young, not the other way around.

“The mountain,” he said, “gave me a beautiful metaphor to better comprehend certain relationships.”

On November 16, 2015, Calgary Arts Development hosted a working session with approximately 30 creative Calgarians from various walks of life. Many of the small working groups voiced the need to gather and share more stories of people living creative lives.

That need has turned into The Storytelling Project.

The Storytelling Project raises awareness about Calgarians who, by living creative lives, are making Calgary a better city, effecting positive change and enriching others’ lives.