Passing on Artistic Knowledge and Traditions

When it comes to artmaking, mentorship matters. From co-productions and incubators for emerging artists to ongoing guidance, artistic mentorship helps pass on the knowledge and traditions of age-old art forms so that they continue to thrive and evolve today. Here’s how some local artists and organizations dedicated to puppetry, traditional Indigenous artmaking and spoken word are carving out lasting legacies.

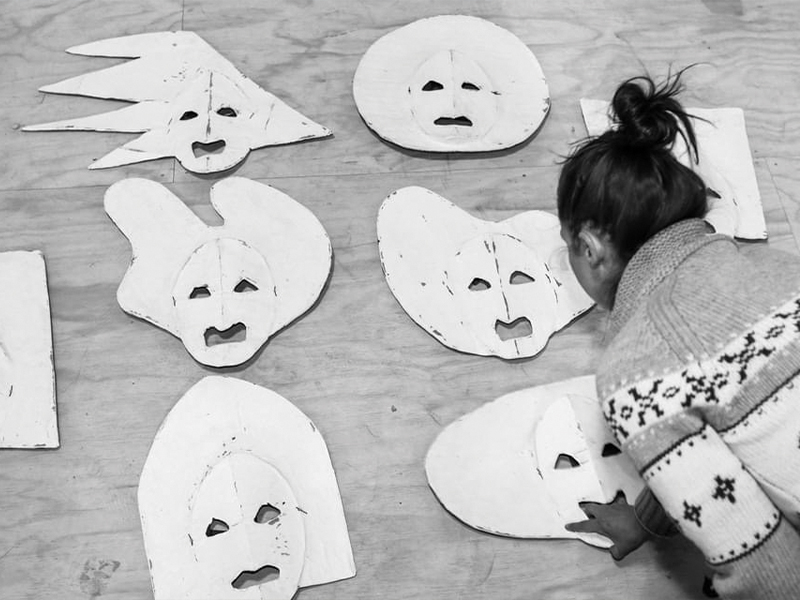

PUPPETRY: IMAGINATION AND PLAY

Left: Pityu Kenderes as the Monster created for Ignorance by the Old Trout Puppet Workshop. Right and middle: OKO Earth Masks by the Canadian Academy of Masks and Puppetry.

For years, Calgary has been known internationally as a hotbed for puppetry, and it has only grown thanks to its diverse collection of innovative puppeteers. Its reputation as a cutting edge community for puppetry was established in the 1980s by Ronnie Burkett, who used original puppetry to tackle challenging subjects such as love, loss and loneliness in a way that took puppetry beyond child’s play, appealing to and connecting with adult audiences.

Calgary’s puppetry companies have continued to push the boundaries of what puppetry can be. Recently, the Fraggle Rock: Back to the Rock reboot of Jim Henson’s popular puppet show was filmed at the Calgary Film Centre. The reboot took place across a sprawling space, including using 3D printers and monorails to bring each scene and character to life while employing a host of local puppeteers to help re-imagine the art of puppetry.

While many people first learn about puppets through early childhood shows like Sesame Street, not all puppeteers go on to learn formally but rather become involved through creative exploration. “Puppetry is a folk art, meaning most of the people doing it haven’t gone through a formal training program, but they do it because they are interested and passionate,” says Peter Balkwill, co-artistic director and co-founder of Old Trout Puppet Workshop. Old Trout is one of Canada’s most prominent puppet theatres and was founded in 1999 by a group of artistic friends with a shared interest in puppetry and re-imagining the art form.

As a folk art, the knowledge of puppetry is spread within the community through festivals, touring shows and workshops hosted by fellow puppeteers eager to pass on their own learned knowledge. Xstine Cook likewise found herself drawn towards mask and puppetry as artistic expressions and has helped grow and share the knowledge of these art forms.

“Albertans definitely embody an entrepreneurial ethos that suits the inventiveness, curiosity and tenacity required by puppetry,” says Cook, who is the co-artistic director of the Festival of Animated Objects (FAO) alongside Balkwill. “My role is to make space for artists to try to experiment, to see what will happen.”

Cook started FAO in 2002 to “build love and awareness of mask and puppetry, to be a platform for local artists, and to be a place for the cross-pollination of ideas, contacts and relationships amongst artists.” Held annually in the spring, FAO hosts 100+ local, national and international artists per year and has an incubator program that supports the development of four new works a year. Cook also hosts and curates the Dolly Wiggler Cabaret — named after Burkett’s term for a puppeteer as a “dolly wiggler” — where each year, 40-plus artists are welcomed into a space where “anything goes.” She has seen artists grow into themselves and their art, evolve to create full-length, sold-out shows, and continue to mentor other emerging artists. In 2003, Cook founded the Calgary Animated Objects Society (CAOS), which mentors five to 10 artists each year and inspires “acts of radical creativity” through making live shows, movies and school residencies.

“By making a safe and welcoming space for anyone interested in these art forms, people are welcome to try, to fail, to try again, to join with others and find a loving audience,” explains Cook. The freedom to fail and try again within a supportive community is what led Balkwill to found the Canadian Academy of Mask and Puppetry or CAMP, as an homage to the Old Trout’s founding members developing the idea for a puppet company at camp. Balkwill acts as co-artistic and educational director alongside puppetry artist Elaine Weryshko, where they foster puppetry throughout Canada with workshops and intensives that support puppeteers in the spirit of play, freedom and imagination.

“Play is mandatory for art, but it has become tough for people because it takes a deeply personal understanding of who you are and what you do to have fun,” says Weryshko.

CAMP also brings in local and global mentors such as David Lane, a theatre artist, puppet maker and original member of Old Trout and Nina Vogel, an award-winning Brazilian artist, who bring unique lessons to presenting puppet shows, crafting puppets and encouraging artists.

Over the years, more local puppet organizations have joined the scene, including Suitcase Theatre Arcade, Mudfoot Theatre and PuppetStuff, further fuelling the art form of puppetry, inspiring and engaging new generations of puppeteers from all backgrounds through community, mentorship and creative freedom.

“The puppet community is exploding with vibrancy right now,” affirms Weryshko. “It’s one of the coolest and most rapidly growing communities with lots of young and old people coming to train and pass on that knowledge.”

INDIGENOUS ART: UNIFYING AND HEALING

Left to right: Kristy North Peigan in cosplay, photo by Colin Smith, and a still from her work Screen Ghosting; Strike-A-Light pouch by Yvonne Jobin; and Stephanie Eagletail, photo by Jared Sych.

In June 2021, the Government of Canada designated September 30 as the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. The day not only marks a pathway to a healthy and united future but also opens the doors for traditional Indigenous art and culture to flourish.

For Yvonne Jobin, Cree artist and founder of Moonstone Creation, an Indigenous art gallery, gift shop and workshop space, Truth and Reconciliation helped further shift Indigenous art and artistic traditions from dying art forms to ones welcomed by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists.

“So many doors have opened for our people in the last 10 years,” says Jobin. “I’ve seen so much growth and positivity, and people wanting to embrace [Indigenous art].”

Jobin learned traditional art methods from Elders and Knowledge Keepers, like decorative art, which includes various forms of beadwork, quillwork, moose hair tufting and fish scale art. Over the years, Jobin has passed along her knowledge, heritage and culture to artists of all backgrounds and cultures through workshops and classes hosted at Moonstone Creation.

“I have always been adamant about helping to promote and preserve the culture through the arts, through all of the classes, and the beautiful things we create,” she says.

Indigenous art has also become an avenue for younger Indigenous artists to educate and raise awareness in new ways. Kristy North Peigan, a Peigan First Nation member and freelance artist, uses her art as an educational tool. As a cosplayer, North Peigan connects to younger audiences while also portraying characters and clothing in a way that speaks to her values as an artist and her Indigenous heritage. In 2023, North Peigan went to the CALGARY EXPO dressed as Wonder Woman with a red handprint across her mouth.

The red handprint has become a powerful symbol of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) movement, used as a sign of solidarity and to represent the thousands of silenced women. By attending a high-profile event in a well-known costume with the lesser-known handprint, North Peigan brings the two ideas together to raise awareness around MMIWG and showcases her work.

“When I encounter people dressed as Wonder Woman, they already love [the character], so I’m not trying to convince them to like me as an Indigenous person, so it’s a great unifier and equalizer,” explains North Peigan.

Art as a unifier is a powerful concept and is becoming a prominent part of modern-day Indigenous art.

When Stephanie Eagletail, an Indigenous fashion designer, was 16, she made her first Pendleton blanket coat under the mentorship of her mother and aunt. Eagletail’s blanket coats began a two-step journey towards self-healing and passing along the art. Eagletail uses the process of cutting and resewing Pendleton and Hudson Bay blankets into coats, both companies with histories of colonization, as an act of decolonization and healing for herself and her family. Each coat honours Eagletail’s culture and traditions by drawing inspiration for her designs from photos and memories of her great-grandparents. Eagletail has also taught over 400 people from Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous organizations the art of coat making and finding healing through the process. Eagletail continues to teach members of local Indigenous communities and Nations across Canada the craft.

“I feel like it’s my gift to share the knowledge of making coats and upcycling and repurposing these blankets,” says Eagletail. “It’s part of intergenerational healing that even after going through all those atrocities, we’re still here today.” Bringing Indigenous culture, tradition and history out of the past is also part of what North Peigan and other Indigenous artists call “Indigenous futurism,” blending traditional and modern mediums to showcase how Indigenous culture is alive now and for future generations.

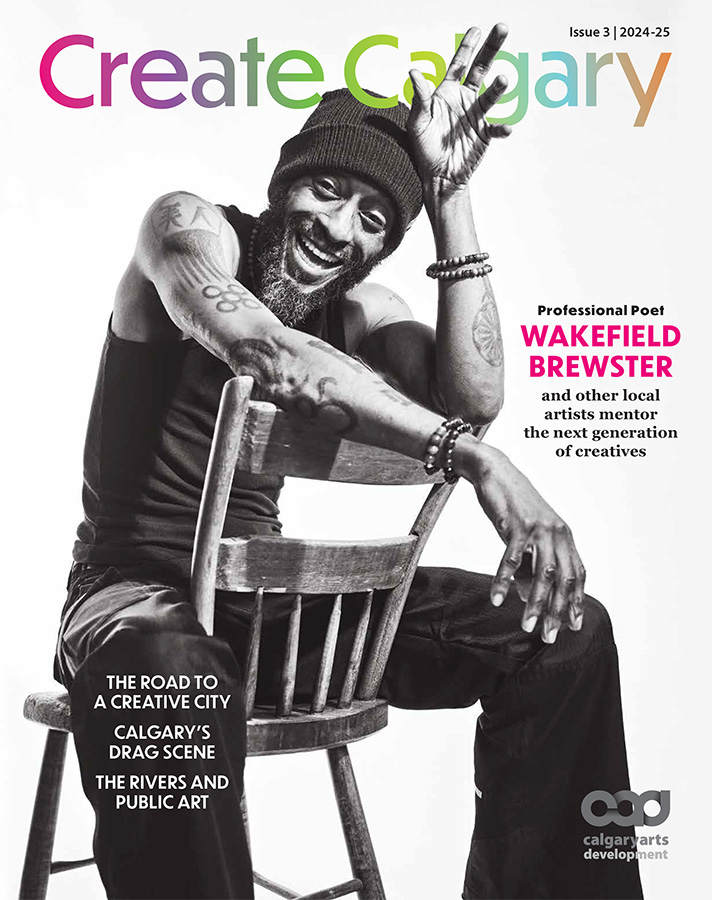

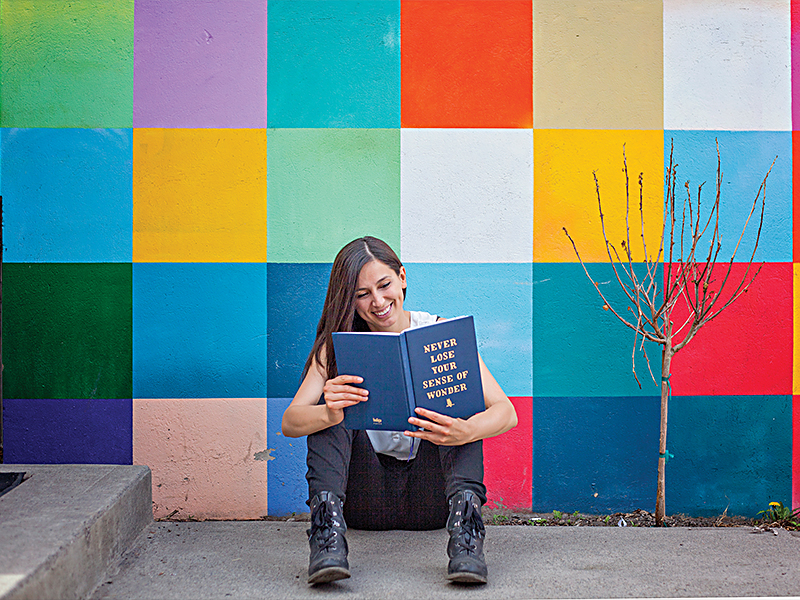

SPOKEN WORD: SPARKING CONVERSATIONS

Left to right: Sheri-D Wilson, photo by Danielle French; Wakefield Brewster; and Miranda Krogstad.

We may not immediately think of speech as an art form, but like all art forms, it is creative and dynamic with the power to engage, connect and entertain audiences.

Some might say spoken word originated from the epic verses spoken in ancient Greece, but the modern version as an art form emerged from movements like the Harlem Renaissance in the early 20th century when Black artists used the medium as a form of social commentary and empowerment as well as in the 1940s and ’50s when Beat Poets in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles, criticized mainstream American life through writing and performing poetry in an authentic, unfettered style. Spoken word artists have also been influenced by jazz, dadaism and surrealism, and the art form continues to evolve.

Spoken word became popular worldwide with Calgarians catching on quite quickly, says Sheri-D Wilson, renowned poet, Calgary’s fourth Poet Laureate, educator and community builder. As a then-aspiring artist, Wilson first travelled around the United States and Europe, discovering spoken word under mentors including Allen Ginsberg, Diane di Prima and William S. Burroughs, who helped Wilson find her own voice. Now, Wilson mentors other aspiring spoken artists along a similar path of self-discovery. “You have to find other voices that you love and listen to everything without judgment. Keep your heart and mind open and explore all possibilities so that you can start hearing your own voice,” explains Wilson.

Helping spoken word artists flourish and explore their authentic voices is what guided Wilson to create safe spaces for spoken word artists to perform without limitation and build community.

Wilson co-founded the Single Onion in 2000, the longest running poetry reading series in Calgary, where renowned Canadian poets and up-and-coming local artists could come together to share their work at open mics and readings, hear different voices and find their own voices. Wilson later founded the Calgary Spoken Word Society and co-founded the Banff Centre’s Spoken Word program. Over the years, Wilson has visited schools and universities to speak about spoken word to hundreds of students and has closely mentored 60 artists.

“Spoken word doesn’t have to follow any rules,” adds Miranda Krogstad, a spoken word artist. “It can be personal and political; it can rhyme or not; it can be uplifting or laugh-out-loud funny. It can be anything you want, allowing anybody to get into it.”

Krogstad co-founded YYSpeak, a spoken word network, in 2013. It began online as event listings for upcoming open mic nights. But over the years, Krogstad has evolved YYSpeak into a “communal and supportive space for spoken word artists” and for the community interested in attending and supporting its artists. Krogstad also works in schools and youth programs, teaching about creativity and empowerment through the art of poetry and in sharing one’s voice. “Spoken word is not just poetry for the poets; it’s poetry for the people,” she says.

Krogstad’s sentiment is shared by many fellow spoken word artists who are changing the narrative of what spoken word can be. For many years, poetry has been viewed as an “elite” art form. Spoken word, however, is bringing about a modern renaissance, making poetry accessible by embracing creative freedom.

Similarly, Wakefield Brewster, professional poet, Calgary’s sixth Poet Laureate and spoken word artist, uses his work as a medium to advocate for literacy and the humanities, healing arts and alternative medicine, awareness for alcoholism and addictions, and mental wellness and recovery.

“The arts are humanities, and the humanities are where we all truly connect,” says Brewster. “Making sure that I can bring my artistic expression in the name of service to different communities is paramount to me wrestling poetry away from the elite and letting the whole world know poetry belongs to them.”

In 1999, during Brewster’s first year of his poetic career, local schools began hosting him to bring his poetic and spoken word knowledge into an educational setting. Since then, he has worked with thousands of students from grade 7 to university level through presentations that he calls “Writing Change Into The World.” He mentors students from writing their work on paper to presenting it on the stage with themes of justice, equality, diversity, accessibility and more. The work is what Brewster proudly calls among his “greatest educational and community projects yet.”

With artists championing the art form by teaching and engaging, spoken word artists and audiences will keep emerging. “Spoken word is going to continue to grow and thrive because you are connecting and responding with it [and the artist] right at the moment, and that sparks conversations,” affirms Krogstad.

This article was originally published in the 2024 edition of Create Calgary, an annual magazine launched by Calgary Arts Development to celebrate the work of artists who call Mohkinsstsis/Calgary home.

You can pick up a free copy at public libraries, community recreation centres and other places where you find your favourite magazines. You can also read the digital version online here.