Calgary Public Art reflects on the life and legacy of Indigenous artist Alex Janvier

The Calgary Public Art team was saddened by the recent loss of one of Canada’s greatest artists whose work is stewarded in the City of Calgary’s public art collection.

Canadian Indigenous artist Alex Janvier, known internationally for his thousands of artworks in private and public collections across Canada and around the world, has died at the age of 89. Officials at the Assembly of First Nations annual general meeting announced the death and held a moment of silence in honour of the artist yesterday with the news of his passing.

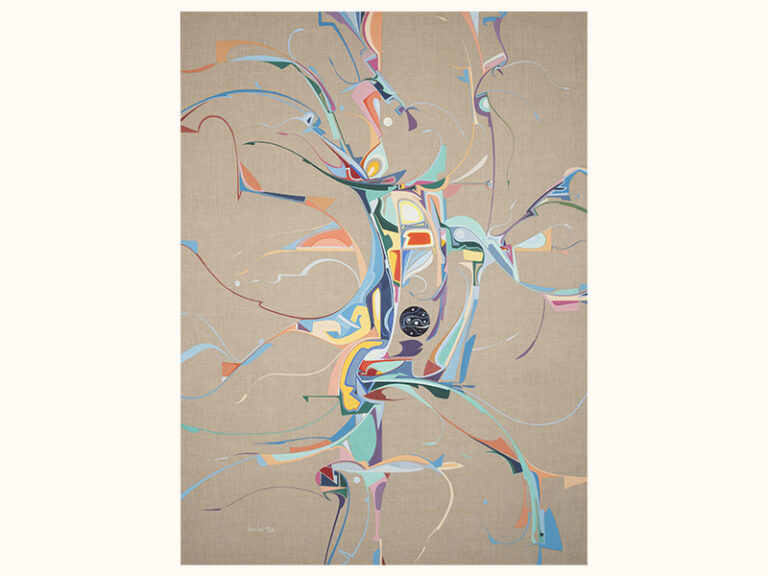

Calgary Public Art was gifted with one of Janvier’s artworks, Hon Kah, in 1995 by the Calgary Allied Arts Foundation, and the painting is on display in the lobby of Mayor Gondek’s office.

Janvier was often called the Michelangelo of Canada because of his unsurpassed talents, especially his ability to paint enormous murals such as his iconic Morning Star – Gambeh Then, a permanent centrepiece of the Canadian Museum of History. The mural rises seven stories above its atrium space and covers 418 m2, which Calgary Indigenous Art Curator, Jessica McMann says speaks to his signature style.

“When I first visited saw his work in his Cold Lake gallery, I can only say I was truly blown away,” says McMann of the Denesuline and Saulteaux artist from Treaty 6 born in 1935 on the Cold Lake Indian Reserve, now Cold Lake First Nations, northeast of Edmonton. “I went to buy a gift for my husband, who was a long-time admirer of Janvier. When you are amid a collection of his work, it is an intensely spiritual experience because of his connection to the land which you can just feel in his work and the fact that he would sign it with his residential school number is just so powerful. To be up close to it is something you never forget.”

At the age of eight, Janvier became a pupil at the Blue Quills Indian Residential School where his artistic talents were immediately undeniable. His lifelong friend, fellow artist Joseph Sanchez tells the story of Janvier being 15 years old painting images of what he called Indian saints, which were of such a high quality that the Vatican insisted on displaying them.

McMann says Janvier’s proficient,, other-worldly skill exploring the landscape of his northern Alberta home, his culture and history, including his own experience of the effects of colonization and residential schools was honed by his endless hours of practice as well as the support of his community.

“Many artists will say his name as their inspiration,” says McMann. “Through his unprecedented success around the world and his prolific work, they see themselves in these positions of huge international respect; they see that as a possibility of their life.”

In 1973, with other First Nations artists Norval Morrisseau, Daphne Odjig and Jackson Beardy, he helped found the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc., also known as the Indian Group of Seven, to bring their work to the mainstream. That opened the doors to a major show in Montreal, and eventually Janvier’s work being shown in galleries across Canada, as well as in Sweden, Paris, London, New York and Los Angeles.

“At that time Indigenous artists paved the way, whether they know it or not, for future Indigenous artists to say, ‘I can do that , too’, as in not just painting what people wanted them to paint but painting their truth,” says McMann. “We still don’t have lots of artists who have reached that level of recognition, and those doors are still not opening wide to individual Indigenous artists, so collaboration is still extremely important.”

Public Art Collection Specialist, Kim Hallis recalls an unforgettable experience of being able to be in the presence of Janvier during his 2018 Glenbow exhibit of the National Gallery of Canada’s traveling show titled Alex Janvier: Modern Indigenous Master.

“He was such a lovely, humble man. Here he was at the centre of this important, national show, with work that is nothing less than stunning, and just the most unpretentious person you can imagine. He’d laugh when people would pronounce his name with a French accent. He introduced himself and said, ‘Oh, I just say Janv-i-er,’ with such a delightful emphasis on the English pronunciation, which tells you everything about how humble and gracious he was.”

McMann adds Janvier, who was known for getting up early and working late into the evening, leaves behind a legacy of a work ethic that will continue to inspire and guide the art community.

“Sometimes people think of artists as working only when they are inspired or working alone all the time. Here is an example of a hard-working professional Indigenous man who was completely dedicated to excellence and often would hire other artists to work on elements of his work, always collaborating and I feel that’s a more accurate depiction and one that is inspiring.”

Having the Hon Kah in the collection, adds Hallis, felt even more poignant after the news of Janvier’s death.

“I feel so lucky and honoured to be able to care for the piece of his we have, I went over and visited it in its space when I learned the news,” adds Hallis. “I just felt deeply thankful for the gifts he left behind and am reminded of the reason why we take care of things the way we do. All the intricate processes and policies and procedures are to protect pieces like this so our kids and their kids can experience what I was able to experience again being in front of Hon Kah. To be in a space with a piece like this is amazing, you can see images of it but to physically be in the space is unparalleled and our work allows for that experience.”

Kathryn Engel is communications strategist for the Public Art team at The City of Calgary. Learn more about the Public Art Collection here.