The Program

Now Touring: Public Art Billboards shines a spotlight on artwork from Calgary’s Public Art Collection by making it part of people’s daily commutes.

The third series of artworks from the collection, titled Collections, Connections and Misconceptions, is on billboards starting March 3, 2025 and shares stories of history, identity and interconnected narratives through art. These nine artworks are curated by Kay Burns and are on display until June 2025. The featured artists include Chris Flodberg, David Rokeby, James Langlands Thomson, Janet Mitchell, Margaret Shelton, Marion Nicoll, Mark Marshall, Ray Van Nes and Wes Irwin.

Curatorial Reflections by Kay Burns

Collections, Connections and Misconceptions

The area surrounding the confluence of the Bow and Elbow rivers that has been the homelands of Blackfoot and other Indigenous nations for millennia became known as Calgary 150 years ago, following the arrival of the North-West Mounted Police. The evolving story of this city, its ups and downs and its search for an identity, is convoluted.

Assembling artworks as an art collection for Calgary began over 100 years ago. That process also has a muddled story. The first commission for a public monument was in 1911 for the Boer War Memorial, unveiled in 1914 in Memorial Park. Over time, architectural features and public monuments became part of Calgary’s evolving visual identity.

Early Calgary was formed with strong imperial attitudes and allegiance to Britain. Colonial perspectives were reflected in the actions of settlers who established the city, seeking to solidify Calgary’s identity within the Dominion of Canada. In western Canada, settlers saw opportunities to claim land and resources, and to build their wealth and influence.

The development of a civic art collection of portable artworks (in addition to the permanent installation of outdoor monuments and architectural elements) began at a grassroots level in the 1920s, driven by individuals, artists and arts groups to create a collection that would be entrusted to the city. The civic collection started with the inclusion of a gallery at the Calgary Public Museum (1927–1935). The collection grew through donations and efforts of many people. But in 1970, over 40 years into the development of that early collection, significant portions were removed and absorbed into collections elsewhere, leaving the civic collection advocates of the Calgary Allied Art Foundation (CAAF) starting over again. This means that everything we currently understand as Calgary’s portable public art collection (displayed in civic offices and public buildings) was collected after 1970.

This digital billboard exhibition features artworks from the Public Art collection to explore interconnections between Calgary, its artists and the creation of the civic collection. The presence of these artworks in the collection and their relationship to the history of the city broadens stories of the past. How are art and community connected? What does it mean to a city’s identity to collect, exhibit and support the creation of art?

Select an artist below to learn more.

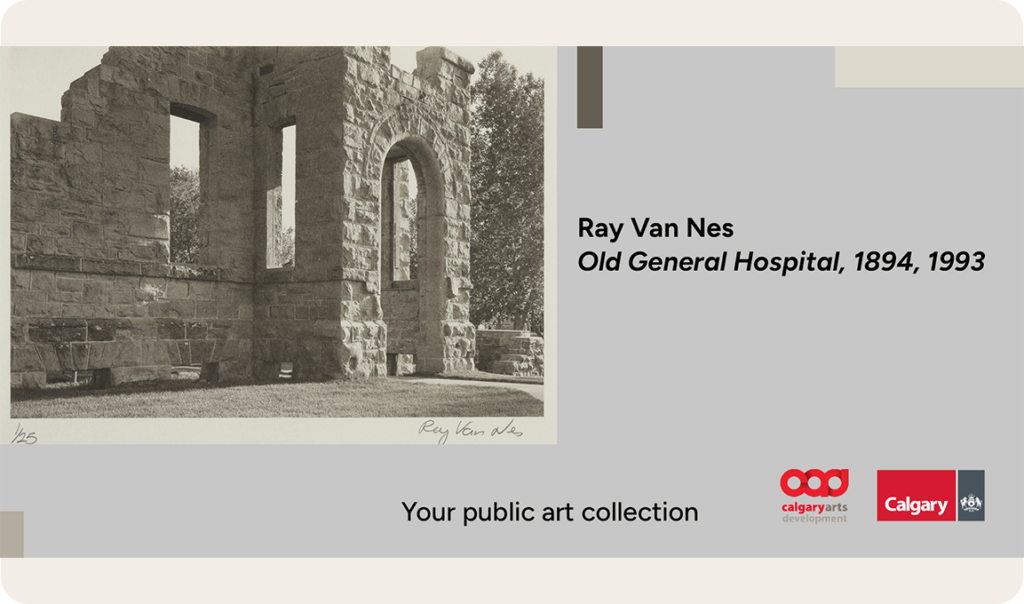

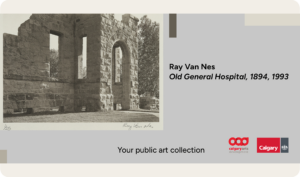

Ray Van Nes, Old General Hospital 1894, 1993, palladium print

Ray Van Nes’s 1993 photograph, purchased by Calgary Allied Art Foundation the same year, shows the remnants of the Old General Hospital at 12th Avenue and 6th Street SE, also known as the Rundle Ruins. The hospital, one of Calgary’s earliest sandstone buildings, was constructed in 1894 just as Calgary was incorporated as a city.

After Calgary’s disastrous 1886 fire, sandstone became a preferable building material, with local quarries supplying the growing city. The advocacy and support of several citizens ensured the creation of this hospital. Jean Anne Drever Pinkham led the fundraising efforts, and Jimmy Smith, a Chinese resident of Calgary, left funds in his estate in 1890 to support its construction.

When a larger General Hospital opened in Bridgeland in 1910, the Old General became an isolation ward for patients with chronic illnesses. Set for demolition in 1971, a group of citizens persistently petitioned to save the building but were not successful in their endeavours. At least not entirely. When the bulldozers came through in August 1973 a few remnants were left in place as part of the new park. The sandstone remnants now stand as a reminder of the many historical structures lost to Calgary’s rapid growth.

Van Nes used a labour-intensive traditional wet photography process, involving metal and chemicals, that dates back to the mid-19th century. This archivally stable photo process represents something long-lasting and durable, in turn alluding to paradoxical questions about how artworks can represent more longevity for history than stone structures.

Mark Marshall, gargoyle (owl), 1913, ceramic

This is just one of approximately 600 ceramic “gargoyles” that were created by Mark Marshall for the Calgary Herald building constructed in 1913. These art pieces adorned this site of news and communications to playfully comment on the activities inside the building and in the surrounding city.

The Calgary Herald first originated in a tent near Fort Calgary in 1883. One NWMP officer was temporarily reassigned from his police duties to help with the printing press for six weeks, drawing on his previous experience as a printer. The tent was the first of eight Herald locations over the years to have witnessed interesting moments in the history of Calgary. Mark Marshall’s gargoyles were featured on the Herald’s sixth location — the 1913 Herald building at 130 7th Ave SW.

Marshall was a sculptor with the British company Royal Doulton, an operation renown for decorative and utilitarian ceramics. The gargoyles included a profusion of flora and fauna (leaves, grapes, snakes, fish, eels, birds, monkeys) as well as caricatures of newspaper employees such as the editor, sub-editor, steno, cleaning woman and typesetter. When the building was demolished in 1972 there was a public outcry regarding the gargoyles and 240 of them were saved. Some ended up on other buildings, some went to private and public collections, and 51 of them are in the City of Calgary collection. These were donated to the civic collection by the Southam Family in 1993.

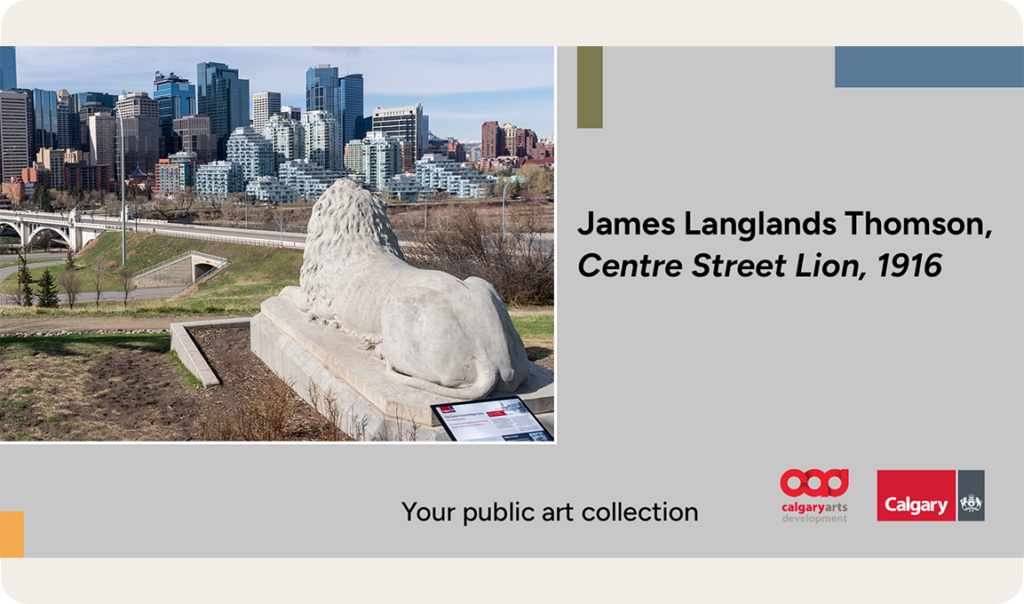

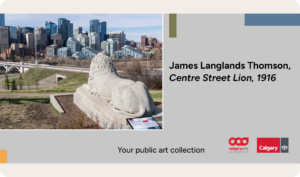

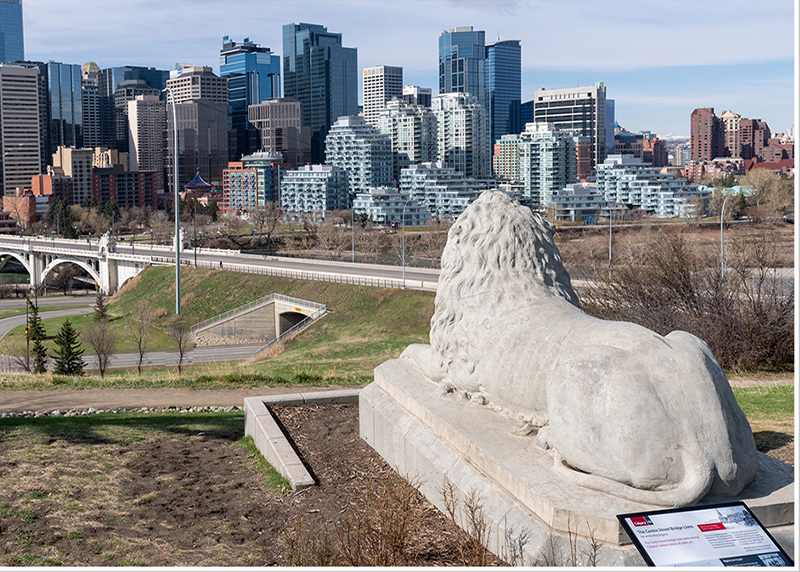

James Langlands Thomson, Centre Street Lion, 1916, concrete

This image shows one of the original Centre Street Bridge lions overlooking the site of its origin. These lions were commissioned in 1916 by the City of Calgary Transportation Department.

At that time, Calgary had been experiencing the repercussions of First World War for a couple of years. The city’s dynamics were shifting due to a population decline following the earlier economic boom. In 1913 Calgary’s population was approximately 90,000. According to the census in 1916 the population was 56,514, of whom 47,710 were classified as British.

The original blueprints for the bridge showed the inclusion of majestic lions and other carvings but the City was planning to eliminate those items because of financial restraints during the war years. However, James Thompson, a city stonemason and labourer who had recently arrived from Scotland, was also a stone sculptor in his spare time. When the City realized that one of their own employees had the skill to produce the ornamental features for the bridge, they reassigned him from his usual duties so he could focus on creating the lions. Lions are a recognized symbol of Britain and its empire; Thompson modelled his lions on the ones in Trafalgar Square in London. The bridge also featured roses for England, thistles for Scotland, shamrocks for Ireland, and bison for western Canada. The lions symbolize early Calgary’s ties to Britain, but over time they also became a lasting icon of Calgary’s identity. They inspired the design of the Calgary Heritage Authority’s Lion Awards, which recognize local heritage conservation.

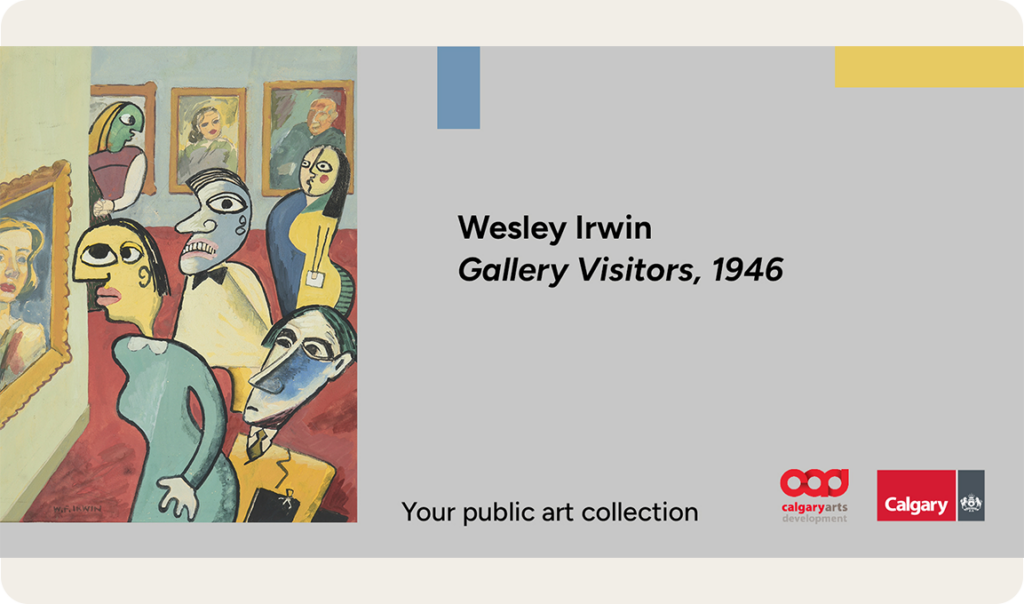

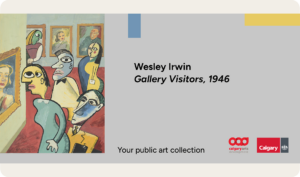

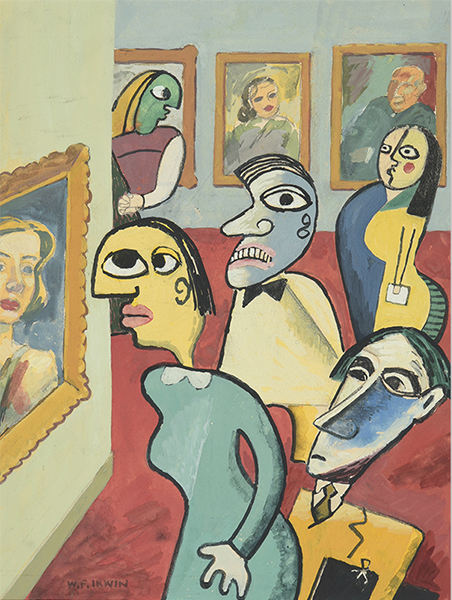

Wes Irwin, Gallery Visitors, 1946, watercolour and gouache

Wes Irwin’s Gallery Visitors, donated to Calgary Allied Art Foundation from Douglas and Jeanette Motter in 1981, is a playful parody on the gallery experience with the visitors appearing as cubist Picasso-esque people examining traditional portrait paintings. Irwin studied art in Chicago and New York. As part of the first generation of Calgary artists navigating traditional and modern art, Irwin sought balance in his practice and teaching. He taught at Western Canada High School from 1935 to 1964.

The date of this work, 1946, was a significant one for artists of Calgary. The Calgary Public Museum, where the civic collection had its origins, had closed in 1935. Following several years of being housed in the library, the collection was moved over to Coste House in 1946 (previously the Mount Royal home of Eugene Coste). The Calgary Allied Arts Council was formed to manage the Coste House Arts Centre and care for the collection. Coste House, “historically significant for the confident cohesion of Calgary’s experimental artists1,” was a lively place with a civic art gallery, community arts centre, workshops and art classes.

Many Alberta artists with recognizable names now had their first exhibitions and/or were participants in group shows at Coste House. It also hosted exhibits on loan from collectors and other galleries, including the National Gallery’s First Biennale of Canadian Painting (1955) that featured several Calgary artists including Maxwell Bates and W.L. Stevenson. Bates and Stevenson had a big impact on local artists through their resistance to mainstream traditions. Their artwork did not sit well within the Calgary art community from the 1920s to 1940s. The dominant practice of art in early Calgary revolved around naturalism and representational English landscape traditions as expounded by artist and teacher A.C. Leighton. Bates and Stevenson were expelled from the Calgary Art Club and were prohibited from exhibiting at the Calgary Public Museum. They were also both excluded from membership in the Alberta Society of Artists when it formed in 19312 with Leighton as its first president. Despite these challenges, they significantly influenced experimental art in Calgary. (Permissions to reproduce civic collection artworks of Bates or Stevenson as part of this Digital Billboard Exhibit are not currently available through the City of Calgary Public Art program.)

1Hudson, Anna, in Kjorlien, Melanie, ed. Made in Calgary: An Exploration of Art from the 1960s to the 2000s, p10

2 Townshend, Nancy, A History of Art in Alberta 1905-1970, Bayeux Arts, Calgary, AB, 2005, p16

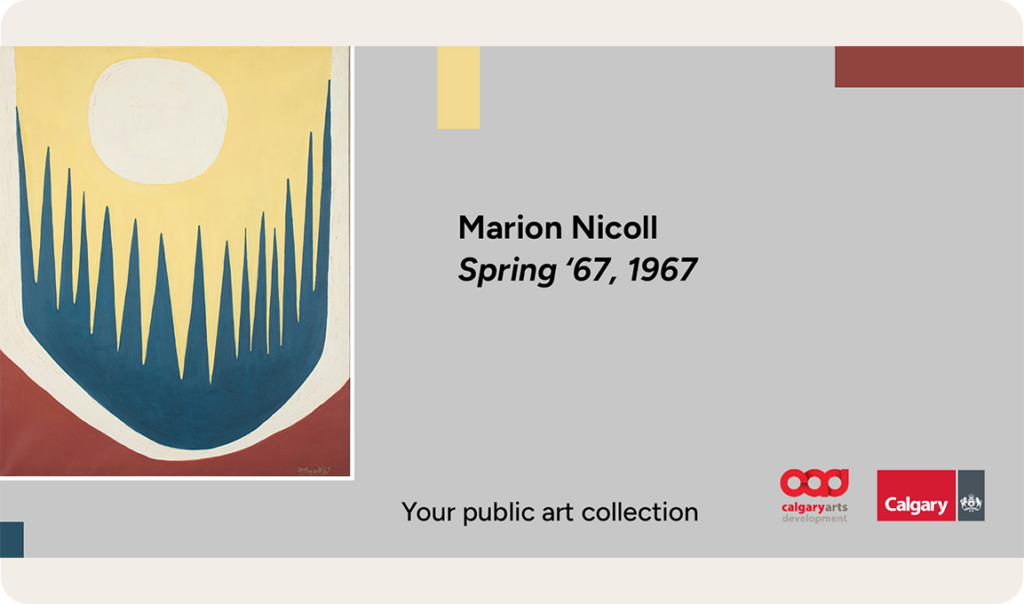

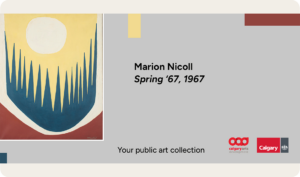

Marion Nicoll, Spring’67, 1967, oil on linen

This large painting created by Marion Nicoll in 1967 was gifted to the collection in 1983 from the Calgary Convention Centre. She and her husband, Jim Nicoll, donated art works to the civic collection for many years and provided an endowment to Calgary Allied Art Foundation (CAAF) in 1986 for the purchase of artworks into the future.

Nicoll influenced hundreds of young artists through her teaching at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art. She is recognized for her contribution to abstract art in Alberta. Before 1958, Nicoll created naturalistic watercolours, drawing partly on her training with A.C. Leighton. Dissatisfied with limitations of realism, she reached out for alternative experiences through classes in New York. Like Bates and Stevenson, she too had discovered that modernism was generally not well received in Alberta before the 1950s. By then, however, younger artists were becoming actively involved in modernism and abstraction.

Nicoll’s later work was inspired by the world around her and life in Alberta. Elements of the natural environment are pared down to essentials to portray seasons, weather, place, and experience. This piece, Spring’67, depicts a sense of joy at the return of springtime sunshine and at the same time evokes the sense of cold that lingers as ice melts during this transitional season.

Throughout the 1960s while Nicoll was exploring abstraction, changes were happening with the civic art collection. The centre had outgrown the Coste House; in 1959 CAAF was established to become the official owner of a larger property. The new centre on 9th Avenue hosted numerous exhibits and expanded collection efforts. By 1969 there were approximately 250 works in the civic art collection. However, the decade of the ’60s in the new building landed CAAF in serious financial difficulties, which dramatically affected the art collection. Artworks that had been donated or purchased by artists and others for the civic collection from the 1920s to 1969, did not remain with CAAF after 1970.

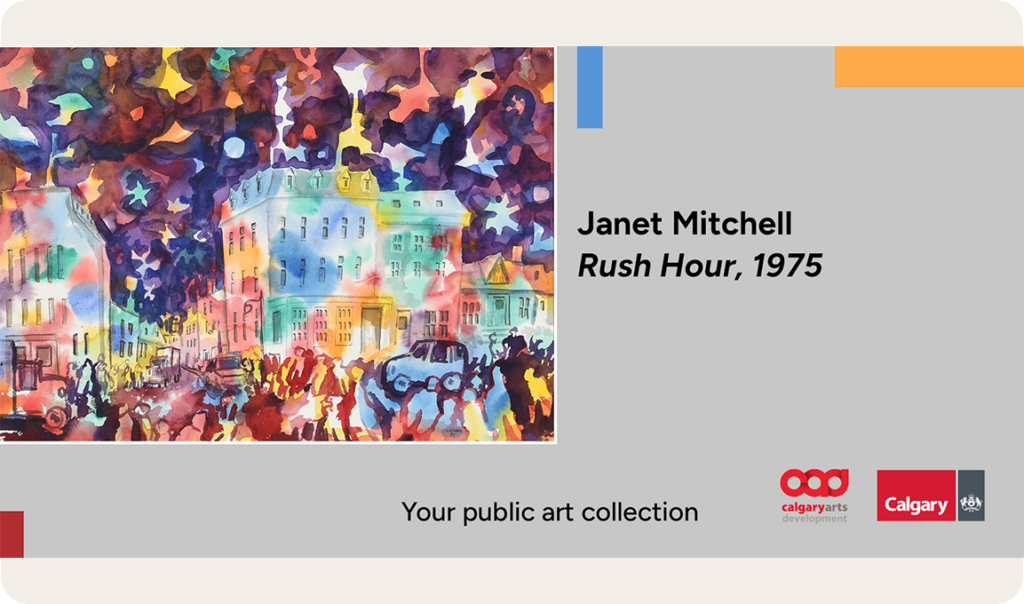

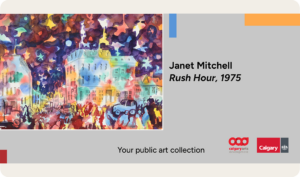

Janet Mitchell, Rush Hour, 1975, watercolour

This watercolour by Janet Mitchell was acquired by Calgary Allied Art Foundation (CAAF) in 1975. There had been four works by Mitchell in the original civic collection that had been surrendered through the complicated financial transaction of 1970.

Eric Harvie, founder of Riveredge Foundation and Glenbow Foundation, purchased CAAF’s building and assets when it was facing insolvency. Complications arose because the sale agreement listed the art collection as part of the assets, rather than as a collection being held in trust. The artworks became part of the Riveredge collection and later transferred to the Glenbow-Alberta Institute. The Bill of Sale3 located within the City of Calgary archives includes 11 pages listing assets, itemizing the building’s furnishings as well as over 250 artworks of the original collection. It also states that CAAF had “unencumbered title to the said goods and chattels and has power to dispose of the same….” The archive also contains correspondence that questioned and disputed the transfer of ownership of the artworks, but no alternative resolution has been reached to this day. In the 1970s CAAF started over again to build a civic collection. The original collection had “reflected the values and history of early Calgary and in its own way, defined what Calgarians considered to be their culture.”4 CAAF retained the H.B. Hill bequest towards art purchases for the collection, and in 1977 Wes Irwin also provided an endowment for the civic collection. By the end of the 1970s CAAF had 24 works in the new collection. Rush Hour, was one of them.

Janet Mitchell had had a studio in the Coste House and was involved in exhibitions with Marion Nicoll and Maxwell Bates; she was one of several Calgary artists perceived to be part of a progressive chapter in Alberta’s history of art. Mitchell was concerned with developing her own personal voice, and her travels brought her awareness of artists such as Paul Klee and Marc Chagall whose work influenced her practice. In 1955, Maxwell Bates described her approach as more intuitive than any other artist5 in Alberta.

3 “Bill of Sale” between CAAF and Riveredge Foundation, July 31, 1970, City of Calgary Archives, Calgary Allied Arts Foundation Fonds, PR90-005, Box 1

4 Calgary Allied Arts Foundation: 20th and 21st Century Cultural Aspirations For A Loved City p26

5 Townshend, Nancy, A History of Art in Alberta 1905-1970, Bayeux Arts, Calgary, AB, 2005, p128

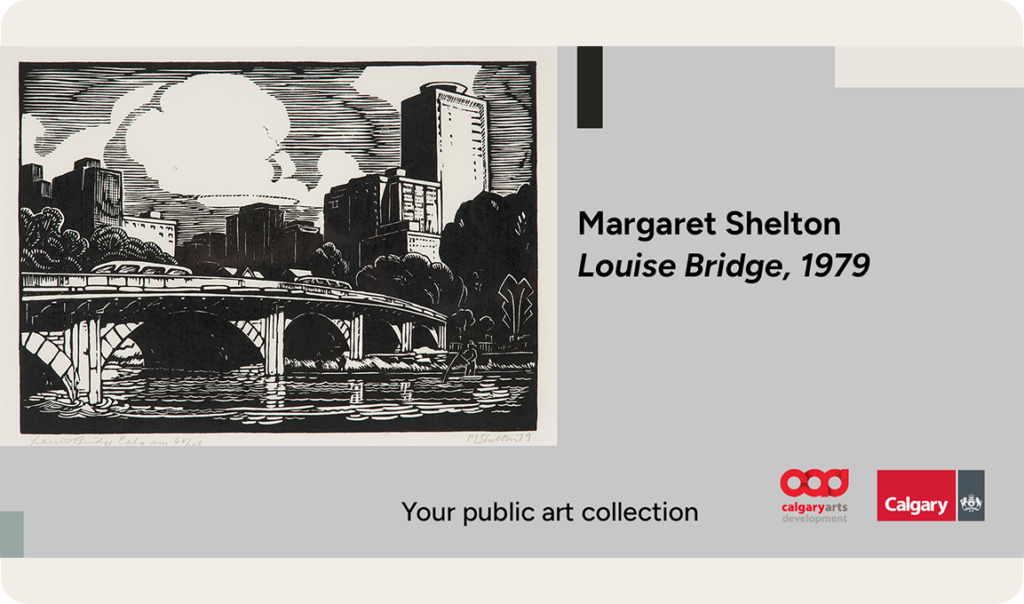

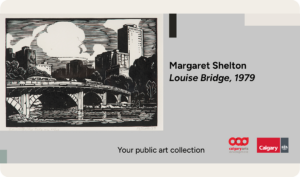

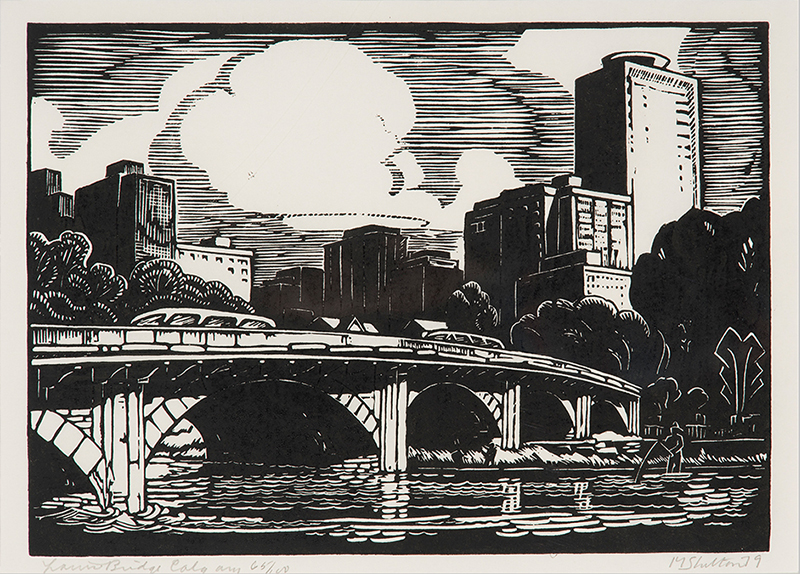

Margaret Shelton, Louise Bridge, 1979, linocut

Like any city that’s built up around a river, the bridges of Calgary play an iconic role in the imagery of artists and the history of place. Margaret Shelton’s 1979 linocut print of Louise Bridge was procured by Calgary Allied Art Foundation (CAAF) in 1988; the current collection now contains 10 of her works. Shelton was a prolific artist and over her lifetime she produced “more than 174 relief or block prints.”6

Shelton’s work is striking and captures the character of place. Her image of Louise Bridge portrays snippets of everyday life, with transit buses heading to and from downtown, and someone leisurely fishing from a small boat. The bridge, also known as the Hillhurst Bridge, crosses the Bow River at 10th Street and is significant to the history of Calgary. The first bridge at this location was made of wood built in 1888, the second was a steel truss bridge built in 1906. The concrete bridge built in 1921 is the current one, as seen in Shelton’s image. A bridge at this site was critical to the expansion of the street rail system in Calgary, used as part of loop joining the north and south sides of the city.

In an unexpected connection, J.J. Hanna was an engineer with the City of Calgary and when he returned from the First World War he “became the city’s resident engineer on construction of the Hillhurst Bridge.” Nearly 50 years later, J.J. Hanna was a member of the Board of Directors of CAAF who signed the July 31, 1970 Bill of Sale (along with G. Crawford) that resulted in the transfer of 250 artworks out of the civic collection, including a piece by Shelton.

6 Laviolette, Mary-Beth, Alberta Mistresses of the Modern, 1935-1975, Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, 2012, p51

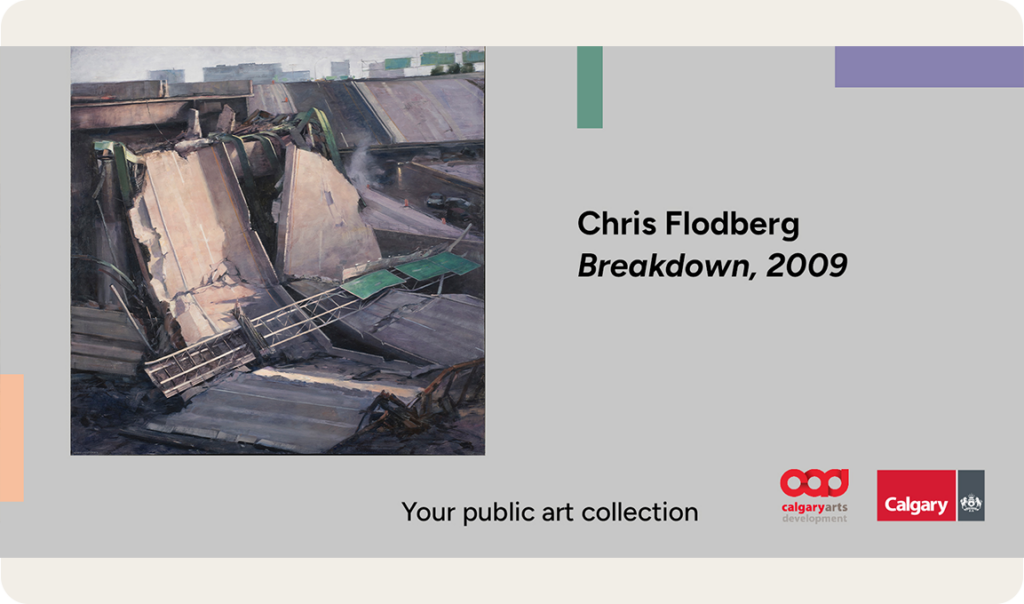

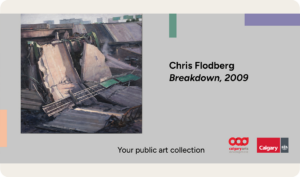

Chris Flodberg, Breakdown, 2009, oil on canvas

Chris Flodberg’s painting Breakdown became part of the civic collection in 2011. It’s an ominous artwork depicting a bridge collapse; metaphorically questioning the societal and environmental repercussions of our actions.

Flodberg’s work has been described in numerous contexts as fin de siècle, which is a European art term to reference the symbolism and decadence of the 1890s; it “expresses an apocalyptic sense of the end of a phase of civilisation.” The image of a crumpled highway bridge with tall buildings in the distance, could be anywhere, any city. Demise captured at a crucial moment, a possible harbinger of greater calamity to come. In a recent email conversation with Flodberg, he describes this painting and others he was doing around the same time as a place where “human technology, the effects of nature, and failure to plan for the future collide.”

The painting alludes to questions about Calgary’s history of boom-and-bust cycles, periods of rapid growth, and rampant resource exploitation. At a time when the city of Calgary is facing infrastructure issues, housing issues, and intensifying crime, this painting feels like a warning — a time to carefully examine the values and relationships we are condoning.

The end of an era is a recurring theme in both Calgary’s evolving history and the story of its art collection. While Breakdown may be advancing difficult questions, there is also the unspoken implication of the potential for new beginnings.

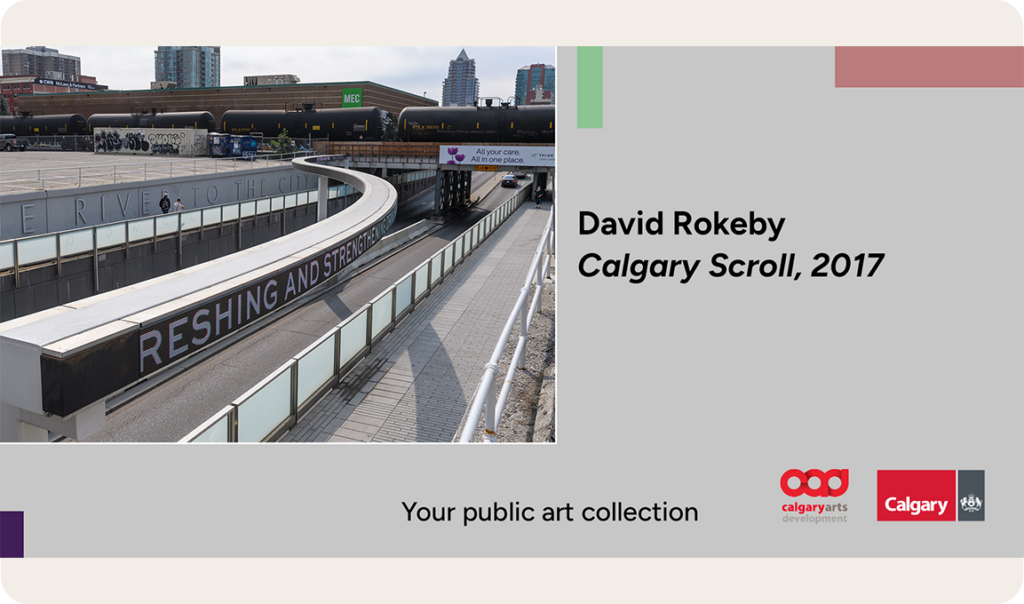

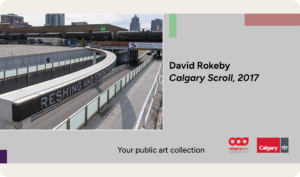

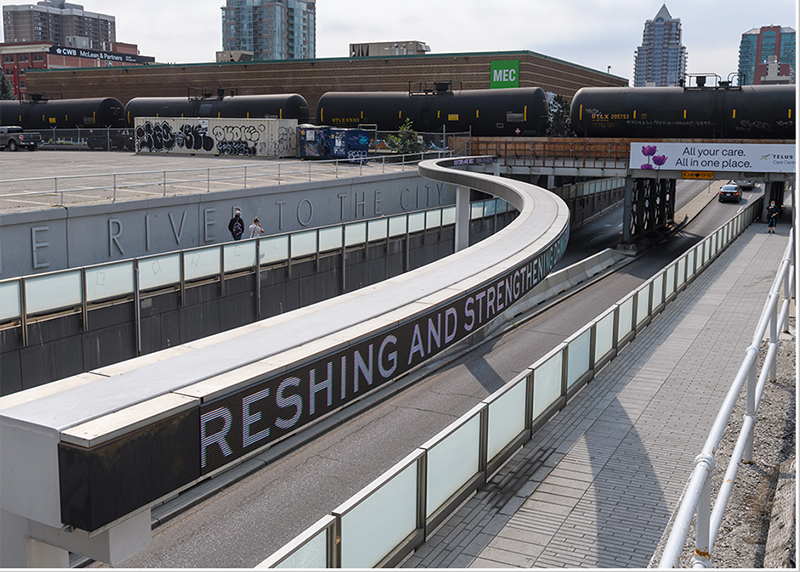

David Rokeby, Calgary Scroll, 2017, steel, aluminum, LED panels etc.

“At about 5 o’clock this morning the new portion of the western bridge over the Bow River was carried away by the impetuous rush of the flood. Two houses floated past at a terrific rate.” — Weekly Herald, Jun 24, 1897.

This is just one of the many quotes from early records offered by David Rokeby’s Calgary Scroll public art installation commissioned by City of Calgary Transportation in 2017. Created 101 years after the City of Calgary Transportation Department commissioned the Centre Street Bridge Lions at a vital junction of the city, this contemporary work offers glimpses into the city’s past from another crossing. Rokeby’s work is at the 8th Street underpass and witnesses thousands of vehicles pass through beneath as countless trains pass over top. Calgary was built around the railway with the core of city bracketed by the Bow River to the north and train tracks to the south. As a result, traversing the river and the tracks became a perpetual challenge for moving people through downtown.

Within this public installation, phrases scroll by, speaking to fragments of the city’s history — its role as a frontier city, its achievements, its challenges, its embarrassments. The project also invites passers-by to influence the feed of information by texting a word to 587-355-2422 into the memory banks to see what will happen. Curious about what newspapers said about trains, or floods, or housing a hundred years ago? Text your topic, and quotes will emerge across the LED panels.

“The money for the payment of the Indians of Treaty No.7 arrived here by yesterday’s train…” — Weekly Herald, September 30, 1885.

For the civic collection, the 2000s saw further modifications. Calgary Allied Art Foundation’s role now is as a facilitator for emerging artists through residencies and exhibitions. A new City of Calgary Public Art Policy was implemented in 2004 (with later revisions) outlining purposes and processes for commissions and acquisitions. The current collection now contains over 1300 works. Public art policies and structures continue to change; and the civic art collection continues to act as a repository of the history of the city, its search for identity, and as a reflection of active involvement by its citizens.

Selected Books and Articles

Armstrong, Peggy, Janet Mitchell Life and Art, Hyperion Press Ltd. Winnipeg, MB, 1990

Kjorlien, Melanie, ed. Made in Calgary: An Exploration of Art from the 1960s to the 2000s, Glenbow Museum, Calgary, AB, 2016

Kwasny, Barbara and Peake, Elaine, A Second Look at Calgary’s Public Art, Detselig Enterprises Ltd, Calgary, AB, 1992

Laviolette, Mary-Beth, Alberta Mistresses of the Modern, 1935-1975, Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, 2012

Laviolette, Mary-Beth, At the Crossroads: Helen Stadelbauer and Wes Irwin, Triangle Gallery, Calgary AB, 2010

Townshend, Nancy, A History of Art in Alberta 1905-1970, Bayeux Arts, Calgary, AB, 2005

Townshend, Nancy, Calgary Allied Arts Foundation: 20th and 21st Century Cultural Aspirations For A Loved City , 2016

Townshend, Nancy, Maxwell Bates: Canada’s Premier Expressionist of the 20th Century, Snyder Hedlin Fine Arts Ltd., Calgary, AB, 2005

Townshend, Nancy, two panels from her exhibition, Maxwell Bates and fellow Expressionist William Leroy Stevenson, Gallery 505, September 29, 2017 – January 25, 2018

Ylitalo, Katherine, 2020 Review of The City of Calgary’s legacy: more than 100 years of collecting art, City of Calgary internal document, 2020.

Selected Archives

“Bill of Sale” between CAAF and Riveredge Foundation, July 31, 1970, City of Calgary Archives, Calgary Allied Arts Foundation Fonds, PR90-005, Box 1

“Agreement” between Calgary Allied Art Council and Glenbow-Alberta Institute, April 8, 1970, City of Calgary Archives, Calgary Allied Arts Foundation Fonds, PR90-005, Box 1

Letter to Mr. H. W. Meech, Devonian Group, from F.D. Motter, Calgary Allied Arts Foundation, October 5, 1977, City of Calgary Archives, Parks and Recreation Fonds, Series V, Box 66

Letter to F.D. Motter, Calgary Allied Arts Foundation, from Mr. H. W. Meech, Devonian Group, October 20, 1977, City of Calgary Archives, Calgary Allied Arts Foundation Fonds, PR90-005, Box 1

Selected Online Resources

https://www.calgary.ca/arts-culture/heritage-sites/scripts/historic-sites.html?dhcResourceId=681

The Story of Calgary’s Centre Street Bridge Lions

https://www.heritagecalgary.ca/heritage-calgary-blog/yycnewspapers

The Story of the Calgary Herald Gargoyles

http://www.calgaryalliedartsfoundation.ca/public-art-collection/endowments/

City of Calgary Public Art Collection

The City of Calgary has an art collection of more than 1,300 works, including: outdoor sculptures, installations integrated into infrastructure, monuments, memorials, environmental art, temporary projects, street art and functional objects. Calgary’s Public Art Collection also includes an assortment of portable art — photographs, paintings, sculptures, glass, installations, ceramic and textiles — that are rotated throughout city spaces and public areas such as parks, plazas, recreational facilities, public buildings and the Plus 15 network. The public art collection has been growing alongside our city, building on the importance of art and storytelling in our collective memory.

At any given time, approximately 80 per cent of the collection is on free public display for Calgarians to enjoy. When artworks are not being rotated through public spaces or out on loan, they are kept in a storage facility where maintenance and conservation work ensures they will continue to be enjoyed by future generations.

The billboards give Calgarians a glimpse at our cultural heritage through artworks featured on these outdoor canvases.

Calgary Arts Development is the commissioning body for new public art projects, while the collection is stewarded by The City of Calgary. Learn more about the collection here.

Where in Calgary are the currently active billboards? Our interactive map will be updated soon.